This article was written by John Cannon at Mongabay.

13 December 2022

Threatened cloud forests key to billions of dollars worth of hydropower: Report

- Payments for the provision of water by cloud forests for hydropower could produce income for countries and bolster the case for the forests’ protection, a new report reveals.

- These fog-laden forests occur on tropical mountains, with about 90% found in just 25 countries.

- Cloud forests are threatened by climate change, agricultural expansion, logging and charcoal production, and studies have shown that the quality and quantity of water that these forests generate is tied to keeping them healthy.

The tiny droplets of condensation in the canopies of the world’s cloud forests are just the first link in a life-giving chain. That water replenishes rivers, streams and reservoirs, filters down to thirsty farmland, and flows through pipes into homes and industry. It is the lifeblood of the human villages, towns and cities downslope, not to mention the rich tapestry of species of plants, animals and fungi that flourish in cloud forest ecosystems.

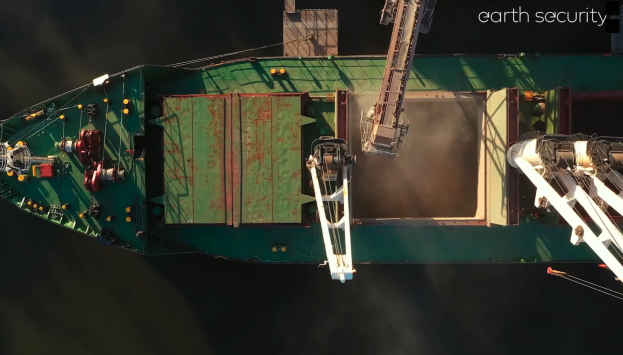

But today, cloud forests are under threat as populations grow and climate change forces farmers to look for cooler climates for key crops, such as coffee. Timber harvesting and charcoal production also endanger cloud forests, many of which are not currently protected. One solution to saving these forests and the water they produce is to generate income for the countries where they exist, according to a new report published Dec. 13 by Earth Security, a U.K.-based consultancy focused on climate and nature-based “asset solutions.”

Cloud forests crown mountains in the tropics, typically at heights of 1,500-3,000 meters (about 5,000-10,000 feet). Mosses often drape the trees are often draped in mosses that aid the forest in collecting water from the fog banks that give cloud forests their name. More than 90% of these forests occur in 25 countries, many of which are less industrialized with struggling economies. In these countries, the report found that nearly 1,000 hydropower dams currently provide electricity to their citizens, more than half of which rely on water that comes from these forests. Hundreds more cloud forest-dependent power stations will come online in the coming years, increasing the value of the electricity they produce to $246 billion over the next decade, according to the report.

The authors, led by Earth Security founder and CEO Alejandro Litovsky, wanted to find some way to leverage these services to benefit the forests and the countries involved. The team isn’t advocating for hydropower, Litovsky said, and he acknowledged that dam construction can cause environmental and social problems, such as community displacement. But the reality is that many countries have dams in place, he added, and new construction, often to achieve goals around low-carbon power generation, is already in the works.

“Could these dams be taxed in some shape or form to provide a revenue stream for the protection of the water source?” Litovsky said. “That makes these forests more attractive to preserve rather than to cut down for other economic purposes.”

He also aims to involve the global investment community to further buttress cloud forest protection.

NGOs and researchers have tried “payments for ecosystem services,” or PES, programs with cloud forests in parts of the world. They’re often locally focused rather than assessing the value countrywide, as Litovsky and his co-authors suggest. And they’ve typically centered on the quality of water provided to consumers, like the multiyear project that environmental engineer and hydrologist Alex Mayer has been involved with in the Mexican state of Veracruz.

“We know there’s a link between forests and water quantity and quality,” said Mayer, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Texas at El Paso in the U.S., who was not part of the Earth Security Report. In the team’s work, “We were able to show that it is the primary forest, the very old cloud forest, that provides the most ecosystem services.”

In Coatepec and Xalapa, two cities in Veracruz, residents paid a fee added to their water bill for the provision of clean water from cloud forests. Mayer and his colleagues revealed that water consumers understood the connection between the protection of cloud forests and having water when they turned on the tap, Mayer said, and they were willing to pay for it.

Still, he added that the connection between those forests and water availability is “much more subtle” than the link to hydropower.

“I think that is pretty important,” Mayer said. “I welcome these very creative thoughts about new ways to finance forest conservation.”

Focusing on hydropower goes hand in hand with the provision of clean, plentiful water for agriculture and other purposes, Litovsky said.

“If you lose this water as a country, you’re going to be in a lot of trouble,” he said.

Clean water is also important to ensure turbines continue to crank out power. Silt and sediment in the water, which increases as cloud forests are cleared or degraded, decreases hydropower plants’ efficiency, Litovsky said.

“As an environmental engineer,” Mayer said, “I can plug that right into an equation and say, this is how many kilowatt-hours you’re going to lose as a result.”

Similarly, functioning cloud forests help maintain the flow of water in dry and wet seasons, Mayer said.

With the current global zeal for carbon markets and offsets, investors are more aware of the importance of forests in general. But questions remain about how effective carbon offsets and trading will be in actually protecting forests, Litovsky said.

“I think carbon alone is probably not going to do it,” he said, “so how do we stack up other values?”

Zeroing in on water’s role in generating power makes the connection between “a very threatened ecosystem” and the provision of water more tangible, especially in the investment community, Litovsky added.

“This is just not really on the radar screen,” he said — that is, until the link between hydropower and healthy cloud forests becomes clearer.

Paulo Bittencourt, an ecologist at Brazil’s State University of Campinas, who was not involved in the Earth Security report, said research shows that cloud forests are “disproportionately important” because of the water-related ecosystem services they provide.

In his view, finding ways to include the value of other uses of water, beyond the report’s focus on hydropower, could be beneficial. “But overall, I think it’s the kind of initiative we need,” Bittencourt added.

Litovsky said he hopes the report will serve as a “practical blueprint” for both investors and countries with most of the world’s cloud forests. The report lays out a plan for the Cloud Forest 25 Investment Initiative, a platform for exchange between cloud-forest countries, including Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Peru, as well as with donors and creditors.

The team also recommends the creation of cloud forest bonds. This financial tool might involve “debt-for-nature swaps,” a pathway to eliminate part of a country’s existing debt in return for conservation commitments. Governments could also use such bonds to borrow or receive funding for specific environment-related results.

With the heightened awareness around nature-based solutions, Litovsky said, “It’s just the right time to introduce something more powerful and much more compelling than the more simplistic carbon lens on forests.”

He said adding this new dimension around the specific services that key ecosystems provide increases the likelihood that they’ll be protected, which is why his team developed the recommendations in the report in the first place.

“The primary motivation was to say, how do we begin to unlock finance for other functions of tropical forests to essentially increase the value of keeping these forests standing?” Litovsky added.

Explore the reports

The Earth Security Index Reports provided in-depth analysis of critical themes across selected industries and market geographies, enabling investors to anticipate and respond to emerging global dynamics. Download and explore the full Earth Security Index reports: